Provings in Homeopathy

Vergleich: Siehe: Prüfungen + Provings

http://www.homeoint.org/morrell/articles/firstprovings.htm

[Burkhard Hafemann]

Das zentrale Kennzeichen der neueren Homöopathie ist die Untersuchung von Heilmittelklassen. Im Falle pflanzlicher Arzneien beispielsweise handelt es sich um

natürliche „Familien", d.h. Gruppen biologisch verwandter Pflanzen und Heilmittel. Durch fortschreitende „Einschachtelung" wird dabei versucht, das für eine Person

am besten geeignete Heilmittel ausfindig zu machen.

Angenommen, die Person benötigt die Arznei Thuja, so wird dies durch mehrere Schritte ermittelt.

1. Es wird bestätigt, dass der Patient tatsächlich ein pflanzliches Mittel benötigt und nicht statt dessen ein mineralisches oder animalisches. Diese Differenzierung gelingt

dabei durch bestimmte Kriterien (Kennzeichen des pflanzlichen Typus).

2. In diesen Schritt wird zweitens festgestellt, dass die Person einer der pflanzlichen Klassen zugehört, in unserem Fall den Koniferen (Kiefernartigen).

3. Beim dritten Schritt bildet die Ermittlung des Reaktionstyps („Miasma"):

Die Arznei Thuja liegt im sogenannten Sykose-Miasma. Wenn die Kennzeichen dieses Reaktionstyps auf den Patienten zutreffen, ist es sehr wahrscheinlich, dass dieser von Thuja profitieren wird.

4. Den letzten Schritt bildet die Abgleichung des klassischen Arzneimittelbildes der Pflanze mit der betreffenden Person.

Unser Beitrag zur neueren Homöopathie betrifft v.a. die oben genannten Punkte 2 und 3. Die Zuordnung von Arzneimittelklassen zu den „vier Elementen" (FEUER, WASSER, ERDE, LUFT) gestattet es, angesichts des Temperaments einer Person die in Frage kommenden Arzneimittelklassen (seien es mineralische, pflanzliche oder animalische) vorab bereits auf etwa ein Viertel einzugrenzen.

Die Koniferen fallen beispielsweise ins WASSER-Element (phlegmatisches Temperament). Nur eine Person, die von ihrem Temperament her ein WASSER-Typ ist, kommt

in der konstitutionellen Behandlung als Kandidat für eine Arznei aus dieser Arzneimittelfamilie, also etwa Thuja, in Frage. In ähnlicher Weise verhält es sich bei mineralischen oder animalischen Typen:

Die Zuordnung von Mineralienklassen oder tierischen Klassen zu den vier Elementen ermöglicht eine deutliche Einschränkung der in Frage kommenden Arzneien bzw. Arzneimittelklassen.

Der 2e zentrale Frage betrifft den Reaktionstyp (das sogenannte „Miasma"?) in welches eine Person fällt.

Die Lehre von den vier Elementen umfasst eine Konzeption von Reaktionstypen (Aktivitätstypen). Und zwar folgen diese Typen einer Dreiheit von Qualitäten:

Impuls gebend (kardinal), fix und beweglich. Indem wir eine Person einer dieser Qualitäten zuordnen, wird zugleich die Zuordnung zu den drei Grund-Reaktionstypen

der Homöopathie möglich: psorisches, sykotisches und syphilitisches Miasma. Dem sykotischen Miasma beispielsweise entspricht die fixe Qualität.

Ein Thuja-Patient wird also im fixen Aktivitätsmodus liegen.

Vorschlag gemacht, das Element und den Aktivitätstyp vom sogenannten Geburtshoroskop abzulesen: Das Sonnenzeichen („Sternzeichen") einer Person gibt dabei Aufschluss über das primäre Element, in dem diese Person liegt, der „Aszendent" bzw. die Hauptachsen im Horoskop hingegen geben durch ihre Qualitäten (kardinal, fix oder beweglich) Aufschluss über das Miasma.

Zuordnung von Pflanzen klassen zu den vier Elementen

Menschen, die konstitutionell auf pflanzliche Arzneien ansprechen, sind empfänglich für vielfältige Gefühle und sind mehr stimmungsgeleitet als mineralische

Typen, sie verlieren häufiger die mentale Kontrolle und leiden unter vielfältigen Befindlichkeitswechseln. Pflanzliche Typen sind schnell berührt, betroffen, beeindruckt,

verärgert, verletzt durch äußere Eindrücke und das Verhalten anderer und leiden seelisch an diesen Dingen.

Wenn wir pflanzliche Arzneien den vier Elementen zuordnen, ist, wie auch im Falle der Mineralien, sowohl deren psychisches als auch körperliches Wirkprofil

berücksichtigt. In diesem Zusammenhang lässt sich auch auf Erfahrungen der traditionellen Vier-Elemente-Medizin zurückgreifen, die Attribute von Pflanzen

wie Farbe, Geruch, Erscheinungsform untersucht hat. Pflanzen mit Nähe zum Feuerelement gelten z.B. als scharf, bitter, würzig, intensiv; sie haben eher leuchtende

Farben (gelbe oder rote Blüten).

Zunächst ein Beispiel einer Elementzuordnung:

Der Lebensbaum gehört zu den Zypressengewächsen innerhalb der Ordnung der Kiefernartigen (= Coniferae/= Pinales). Die Kiefernartigen wiederum sind

Teil der Nacktsamer (Gymnospermae). Das Persönlichkeitsprofil des typischen Thuja-Patienten lässt sich folgendermaßen umreißen:

Psyche: Empfindsame Menschen, die sich oft in einer diffusen Weise wertlos oder schuldig fühlen. Sie entwickeln eine Abneigung gegen sich selbst, die im Extremfall

bis zum Selbst-Ekel gehen kann. Thuja zieht sich gerne in seine Privatsphäre zurück und kapselt sich ab. Mitunter kann er ungeduldig, bockig oder wütend reagieren.

Diese Leute haben häufig einen Bezug zum Spirituellen bzw. eine stark intuitive bis mediale Wahrnehmung. Im weiteren Verlauf der Störung werden sie zunehmend

unsicher, konfus und depressiv.

Körperliche Beschwerden: verfroren, träge-blockiert oder in Eile, trockene, gespaltene Haare, weißliche Lippen; gelbe, blasse, fleckige, ölige Haut, oft mit Pickeln;

Warzen im Gesicht und an Extremitäten

Die Nähe zum phlegmatischen Temperament/WASSER-Element sticht ins Auge; der Bezug zu den flüssigen Verteilersystemen, die Beschwerden in den

Bereichen WASSER l, WASSER 2 und WASSER 3 werden deutlich; auch die Signaturen des immergrünen Baumes deuten in diese Richtung. Wir ordnen den

Thujabaum, wie auch andere Vertreter der Kiefernartigen, dem Wasserelement zu.

[Léon Scheepers]

Following the guidelines of subcommittee proving of the E.C.H. (

European Committee of Homoeopathy).

• Monocentric: proving organised in one centre.

• Non-randomized: everybody knows from everybody that he/she is taking

the verum. No placebo was taken.

• Double blind: nobody

participating at the proving (provers, supervisor, director) knows the nature

of the verum proved.

• Non-controlled. No control group/no placebo.

• Pre-observation period: observation period of two weeks before the

intake of the verum.

• No cross-over: only the verum is taking, in a 30K dilution in 6 takes

during two days.

• Proving takes place under the name of “self-experience” and not under

the name “proving” or “medical experiment” because other wise an ethical

commission has to

give his advice.

[Jan Scholten]

1. Sense Provings

Sense provings is a kind of proving I developed in order to get good

pictures of remedies in a short time.

This was needed to get an idea of a vast array of remedy pictures.

Format

A plant in flower is picked and experienced in as many ways as possible.

The experience is visual by looking at it;. The smell, taste and touch of the

plant are experienced.

The name of plant is experienced. All these influences give an

impression on the prover who meditates on all of them.

Advantages

1. Relatively little investment is needed, about one hour.

2. The format gives full focus, gives a strong signal.

3. There is little noise.

4. Sense provings have the best cost benefit ratio.

5. A mother tincture can be made by a pharmacist to produce the

potencies for use in practice.

Disadvantages

1. Personal aspects of the prover can distort the picture.

2. The result is very dependent on the prover quality.

Comment

1. This is mostly done with Plant remedies.

2. It is a good way of doing a proving with one prover.

3. Sense provings have helped me a lot in bringing forth the Plant

theory as expressed in my book Wonderful Plants.

https://ir.dut.ac.za/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10321/667/Hansjee_2010.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[Sharad Hansjee]

2.1.4.1

Dream proving is defined as a systematic procedure which entails getting

in touch with the dynamic influence of the remedy and focussing on and

observing the remedy’s influence on the vital force, in the form of symptoms,

with dreams being the important focus (Dam, 1998). These provings focus upon

eliciting the unconscious play of

dreams. The notion is that the dream state is altered by the proving and

that it is a reflection of the mental and emotional state of the prover

(Herscu, 2002) as well as a

means of access to deeper aspects of the remedy picture.

Although the focus is on dreams, other symptoms are not excluded

(Kreisberg, 2000). Brilliant (1998:113) is of the view that dreams are feelings

and to interpret them can

be treacherous. There are limitations to dream provings related to

whether the dream is part of the picture or all of the picture of the substance

that is being experienced

(Pillay, 2002).

2.1.4.2

Meditation proving establishes a meditation group that meet together to

meditate a few times before a proving. The idea is that the group meets

together to form a single consciousness. The meditative state makes the prover

group more attuned to their individual selves and thus able to pick up

variances in the mental, emotional and physical states. The substance can be

ingested or be in close proximity to the meditation group (Herscu, 2002).

Scholten (2007) was cautious in using the data gained from meditative

provings unless they were verified in clinical cases. The lack of a scientific

basis in the data was noted as recordings are provers imaginations and

manifestations on their meditation and on this basis he discarded them.

2.1.4.3

In seminar provings the remedy is administered to a group of people a

few days prior to or during attendance at a seminar. The effects of the dose is

then discussed during

the seminar. The proving thus reveals the unconscious level of the

remedy and its symptomatology on the mental, emotional and dream levels which

are then discussed

(Herscu, 2002).

2.1.4.4 C4

Trituration provings are carried out in groups during a trituration

process where the trituration is carried out by hand. Provers grinding the proving

substance experience the symptoms of the remedy although the identity of the

substance is kept hidden (Hogeland and Schriebman, 2008). A recent C4

trituration proving of the Protea cynaroides

by Botha (2010) was conducted at the Durban University of Technology.

Botha (2010) gathered clear and verified data in this trituration proving so as

to evaluate the effectiveness of the methodologies employed during the

trituration. This proving was conducted as a double blind placebo controlled

trial in accordance with the proving methodology as set out by Sherr (1994).

2.1.5 Randomised controlled trials (RCT) and provings Wieland (1997)

asserts that Hahnemann’s provings have demonstrated reliable results as tested

by the clinical application of these remedies, although his protocols can be

regarded as unreliable according to the modern standard measures of clinical

trials. He argues further that the purpose of RCT is to demonstrate the

efficacy and safety of a drug compared to placebo in terms of statistical

significance. The key components of a RCT is the double blinding, placebo

control and crossover technique (Dantas, 1996).Dantas (1996: 232) explains the

importance of placebo control in the perspective of provings as the

only means to effectively assess the effects of the test substance

specifically. He further recommends that the placebo control material undergoes

the same manufacturing process only without adding the active ingredient. He

suggests that this is the only way that probable pathogenetic effects can be

properly associated with the presence

of the original substance in the preparation.

Placebo control is accomplished by administering a dose of the placebo

which is identical to the verum, in both gustatory and visual sense, to a

percentage of the placebo

group thus to accurately evaluate which symptoms are produced due to the

verum or the placebo.Sherr (1994: 37) believes that the placebo has three major

benefits:

1. It distinguishes the pharmacodynamic effects of a drug from the

psychological effects of the drug itself.

2. It distinguishes the drug effects from the fluctuations in disease

that occur with time and other external factors.

3. It avoids „false negative‟ conclusions i.e. the use of placebo

tests the efficacy of the trial itself. Vithoulkas (1998) states that the

double blinding or masking technique ensures that the codes identifying the

verum and placebo groups remain hidden from both the researcher and the provers.

Sherr (1994) makes a comparison of homoeopathic provings to the first

phase of clinical drug trials. The first phase is where new drugs are

experimented upon healthy volunteers to examine the pharmacodynamics,

pharmacokinetics, tolerance, efficacy and safety. Homoeopathic drug provings

can thus be conducted as they conform

to the biomedical model by incorporating placebo control, double

blinding and crossover.

Hahnemann in the “Organon of Medicine” presents basic guidelines for

ascertaining the medical actions of a substance. These are listed below:

The medicinal substance must be known for its

purity;

Provers should take no medicinal substances

during the proving;

The provers diet must be simple, nutritious and

non-stimulating;

Provers must be reliable, conscientious, able

to clearly and accurately record their symptoms while being in a relatively

good state of health.

Provers must be both male and female.

The proving substance should be in the 30th

centesimal potency;

All symptoms need to be qualified in terms of

the character, location and modalities;

To prove a substance multiple provings should

be done on the substance including provers of both genders and various

constitutions;

Moderate proving doses yield better results and

are safer than large doses;

During the proving all ailments and alterations

should be attributed to the proving substance;

Provers should keep detailed proving journals;

and Provers should be interviewed daily by the supervising physician.

Many authors have considered that since the Hahnemannian era, provings

have deteriorated in quality and methodology (Sherr, 1994/Vithoulkas,

1998/Walach, 1994).

Sherr believes that provings carried out in the 20th century

have lacked the refinement of earlier provings. As a result he asserts that

there are few refined provings,

the rest of the materia medica containing partial provings or

toxicological reports (Sherr, 19949).

There has been great debate about the best protocols to be used for

provings today. The growing interest in provings and the need to present a

consistent front to a

sceptical scientific world has led to attempts to develop general

guidelines and minimum standards for drug proving protocols, such as the

efforts by the Drug Provings

Group of the European Committee for Homoeopathy at five symposia since

1992 (Wieland, 1997: 231). The aim is to produce a scientific standard for good

homoeopathic drug provings (Wieland, 1997:231).

De Schepper (2001) expounds the importance of conducting reliable

provings. He also employs the basic protocols as laid out by Hahnemann, but he

further details the essentiality of prover selection, potency, substance and

the duration of the provings.

In 1994, Jeremy Sherr published the 1st edition of his book

entitled “The dynamics and methodology of provings”. This book covers every

topic that is relevant to a good proving protocol. Herein is found clear and

detailed guidelines to conduct a proving.

The International Council of Classical Homoeopathy (ICCH) (1999:35) also

recommends Sherr’s proving methodology to perform a thorough and reliable

Hahnemannian proving.

The ICCH (1999:16) further expounds that the aim of the homoeopathic

drug proving is to elicit, observe and document proving symptoms which are

essential for the prescription of a homoeopathic remedy according to the law of

similars. The drug proving thus serves to broaden knowledge about

insufficiently proved remedies and introduce new remedies to the materia

medica.

According to the ICCH the aim of the homoeopathic drug proving is to

gain knowledge about the innate character of a drug thus obtaining a remedy

picture which is of

good quality. The symptoms are then collated and communicated to the

homeopathic community so that they can be clinically verified.

This means that a symptom which has occurred in a drug proving can now,

if occurring in a sick patient, be alleviated by the proved remedy, which

produced the proving symptom after the administration of it. Vithoulkas (1998:

97) mentions that during a proving, one introduces into the organism a

substance that is sufficiently high in concentration that disturbs the organism

and mobilises its defence mechanism. The defence mechanism then produces a

spectrum of symptoms on all three levels of the organism i.e. mental, emotional

and physical. The symptoms thus produced characterise the unique nature of the

substance. In order for a drug to be fully proved it should

first be tried on healthy persons in toxic, hypotoxic, and highly

diluted and in potentised doses. The symptoms produced from the drug are

recorded on all three levels.

The proving methodology for this proving was adapted from the proving

methodology of Sherr (1994).

http://www.interhomeopathy.org/archives-by-category?c=provings

Scientific Provings

Materia Medica

Toxicology

Proving Data

Clinical Verification

Toxicology

Ethnobotany

Accidental poisonings

Provings

Methodologies

Blinding and Placebo control

Protocol and Posology

Placebo control is controversial

Wieland (1997) - modern scientific investigation

techniques may hinder the pursuit of

Smith (1979) - suggests that

Hahnemann and his followers were aware of the effect of suggestion, but saw it

as inconsequential and chose to ignore it.

Jansen (2008) - it

would be more efficient to give all participants verum. Reliable results can be

obtained by comparing the proving results with the baseline symptoms

of each prover, by utilising a

placebo run-in phase and by excluding old symptoms of the prover.

Walach et al. (2004: 182) investigated whether the proving symptoms were

the result of local, non-local or placebo effects

Conclusion, that what was experienced during the proving was different

from mere background noise.

Walach, 1997: Advocates the importance of using both qualitative and

quantitative methods when designing the trial and suggests the use of a double

blind, placebo controlled study.

Signorini et al. (2005) investigated the difference between placebo

controlled trial and traditional trials lower number of mental symptoms in the

placebo group compared to the verum group unusual symptoms did not arise in the

verum and placebo in a similar way.

They concluded that the placebo group seemed important for the selection

of real symptoms.

Rosenbaum et al.(2006: 216) Significant differences between the

narratives of the placebo and verum groups

Verum group tend to use expressions such as ‘I‘ve never felt that

before, Those weren‘t my symptoms‘ and ‘My headache is completely different‘.

Placebo group seem to have vaguer descriptions and are not able to

describe the symptoms and modalities clearly during cross-examination.

Emphasise the importance of personally verifying each of the symptoms

elicited during the proving.

Proving Protocol and Posology

PHYSICAL DOSE REQUIRED

Blinded: Single, Double or Triple

Unblinded

NOPHYSICAL DOSE REQUIRED

Dream

Meditative

Trituration

Gold standard - ICCH (1999)

Healthy volunteers that use no drugs, have no mental pathology and have

been clear of any homoeopathic remedies for at least three months

A comprehensive case must be recorded prior to the trial detailing all

past symptoms and states

Participants must be over the age of 18 and pregnant and breast-feeding

women are excluded

The group must consist of homoeopaths or homoeopathic students, but may

also include provers from a non-homoeopathic background to balance the group.

The number of provers must be

between 10 and 20

The substance must be sourced from a

natural source free from pollution. The precise origin of the substance should

be carefully detailed, including when, where and

how it was obtained, the name,

species, gender, family and other pertinent data

They recommend using two to three

potencies during the proving, as well as using a placebo control (10 to 30%) as

- a means to increase provers‘ attention.

Relative Efficacy:

Tested three methodologies (2008 - 2009)

Single blind C4 trituration – no physical dose, 2 groups of 10 provers

Double-blind Placebo controlled - 6 doses over 2 days, 2 groups of 15

provers (5 placebo and 10 verum)

Single blind Dream proving - 1 dose daily for 3 days, 2 groups of 10

provers

Results

Double blind Placebo controlled

group elicited the most verifiable symptoms, covering 36 repertory chapters

An updated version of the

methodology developed by Hahnemann and is able to accommodate a 21st century

life style.

The duration of the proving varies according to the nature of the

proving substance, but normally lasts for four to six weeks.

Limitations of this methodology

Strict exclusion criteria

Longer duration

Complying with most of the ICCH

regulation regarding provings and the ethics of provings. It is also placebo

controlled, which makes it admissible under phase

one clinical trials.

C4 and Double blind methodologies

are equivalent in 25 of those chapters, only differing with regards to symptoms

that take a longer time to develop e.g.

Digestive disturbances,

The C4 limited to the four hours during which

the trituration takes place and consequently few symptoms are experienced once

the trituration have been completed, thus a paucity of more insidious symptoms,

limited to those provers who are very sensitive to the substance and would

react to the olfactory mode of medicine administration.

Also confirmed Sherr‘s (1994: 16-7)

observation that provings offering a -short cut to an inner essence lack the

larger totality of physical, general and long term

symptoms.

The advantages short duration of the

proving, relative scarcity of long term effects.

The C4 methodology seems to favour

the chapters dealing with the senses, evident in the Ear, Eye, Hearing, Mouth,

Nose, Skin and Vision chapters

Dream methodology indicated the

least amount of chapter affinities, eliciting mainly Mind, Dream and General

symptoms, but not as prominently as the other

methodologies

Represents

the sentiments of group provings, seminar provings and meditative provings

Minimum dosages are administered

Proving takes place in the

subconscious mind, represented by dreams and imagery

Adjustable to suit any time frame

and is less rigorous

Disadvantage

standardisation of the method nearly

impossible

The verum portion elicited 63% of the total rubrics compared to the

placebo portion which only elicited 28%

Reproducibility

Hypothesis: Proving symptoms are reproducible when applying identical

proving methodologies in consecutive years.

The results of statistical tests reflected a reasonable level of

reproducibility

BUT different provers would result in different symptoms due to their

individual susceptibility and sensitivity to the proving substance.

Not one of the groups that exhibited a reproducibility level of less

than 50%

The verum portion elicited 63% of the total rubrics compared to the

placebo portion which only elicited 28%.

2.1.4.1

Dream provings

The dream proving is defined as a systematic procedure which entails

getting in touch with the dynamic influence of the remedy and focusing on and

observing the remedy’s influence on the vital force, in the form of symptoms, with

dreams being the important focus (Dam, 1998). These provings focus upon

eliciting the unconscious play of dreams. The notion is that the dream state is

altered by the proving and that it is a reflection of the mental and emotional

state of the prover (Herscu, 2002) as well as a means of access to deeper

aspects of the remedy picture. Although the focus is on dreams, other symptoms

are not excluded (Kreisberg, 2000). Brilliant (1998:113) is of the view that

dreams are feelings and to interpret them can be treacherous. There are

limitations to dream provings related to whether the dream is part of the

picture or all of the picture of the substance that is being experienced

(Pillay, 2002).

2.1.4.2

Meditation provings

These provings establish a meditation group that meet together to

meditate a few times before a proving. The idea is that the group meets

together to form a single consciousness. The meditative state makes the prover

group more attuned to their individual selves and thus able to pick up

variances in the mental, emotional and physical states. The substance can be

ingested or be in close proximity to the meditation group (Herscu, 2002).

Scholten (2007) was cautious in using the data gained from meditative provings

unless they were verified in clinical cases. The lack of a scientific basis in

the data was noted as recordings are provers imaginations and manifestations on

their meditation and on this basis he discarded them.

2.1.4.3

Seminar provings

In this proving, the remedy is administered to a group of people a few

days prior to or during attendance at a seminar. The effects of the dose is

then discussed during the seminar. The proving thus reveals the unconscious

level of the remedy and its symptomatology on the mental, emotional and dream

levels which are then discussed (Herscu, 2002).

2.1.4.4 C4 trituration provings

The C4 trituration provings are carried out in groups during a

trituration process where the

trituration is carried out by hand. Provers grinding the proving substance

experience the symptoms of the remedy although the identity of the substance is kept hidden

(Hogeland and Schriebman, 2008). A recent C4 trituration proving of the Protea

cynaroides by Botha (2010) was conducted at the Durban University of

Technology. Botha (2010) gathered clear and verified data in this trituration

proving so as to evaluate the effectiveness of the methodologies employed

during the trituration.

This proving was conducted as a double blind placebo controlled trial in

accordance with the proving methodology as set out by Sherr (1994).

2.1.5 Randomised controlled trials (RCT) and provings

Wieland (1997) asserts that Hahnemann’s provings have demonstrated

reliable results as tested by the clinical application of these remedies,

although his protocols can be regarded as unreliable according to the modern

standard measures of clinical trials. He argues further that the purpose of RCT

is to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of a drug compared to placebo in

terms of statistical significance. The key components of a RCT is the double

blinding, placebo control and crossover technique (Dantas, 1996).

Dantas (1996: 232) explains the importance of placebo control in the

perspective of provings as the only means to effectively assess the effects of

the test substance specifically. He further recommends that the placebo control

material undergoes the same manufacturing process only without adding the

active ingredient. He suggests that this is the only way that probable pathogenetic

effects can be properly associated with the presence of the original substance

in the preparation. Placebo control is accomplished by administering a dose of

the placebo which is identical to the verum, in both gustatory and visual

sense, to a percentage of the placebo group thus to accurately evaluate which

symptoms are produced due to the verum or the placebo.

Sherr (1994: 37) believes that the placebo has three major benefits:

1. It distinguishes the pharmacodynamic effects of a drug from the

psychological effects of the drug itself.

2. It distinguishes the drug effects from the fluctuations in disease

that occur with time and other external factors.

3. It avoids „false negative‟ conclusions i.e. the use of placebo

tests the efficacy of the trial itself.

Vithoulkas (1998) states that the double blinding or masking technique

ensures that the codes identifying the verum and placebo groups remain hidden

from both the researcher and the provers.

Sherr (1994) makes a comparison of homoeopathic provings to the first

phase of clinical drug trials. The first phase is where new drugs are

experimented upon healthy volunteers to examine the

pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, tolerance, efficacy and safety.

Homoeopathic drug provings can thus be conducted as they conform to the

biomedical model by incorporating placebo control, double blinding and

crossover.

The homoeopathic proving of Dendroasp is angusticeps 30CH was carried

out as a randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled trial on a proving population

of 30 healthy volunteers.

24 of the provers were in the experimental group and they received the

potentised snake venom. 6 provers were in the control group and they received

the placebo.

OTHER PROVING METHODOLOGIES

There are many different types of provings that help gather information

about a remedy. Each type of proving has its own strengths and weaknesses.

2.4.1 Trituration proving

The remedy is prepared by the process of trituration followed by

observation of the effect of the remedy. It consists of a group of six provers.

C4 trituration provings are a controversial method of determining the

therapeutic value of homoeopathic remedies. This method is advantageous as it

can be proved in hours instead of months or weeks compared to the traditional

methods of provings. There is insufficient research to indicate if the results

of these two methods can be compared (Goote, 2011).

The C4 proving method does not make use of the traditional method of

testing a substance which is on a group of healthy individuals, but is

conducted individually or on

a group of provers during the trituration process. The prover should

establish a resonance with the substance so that the spiritual level of the

remedy can be experienced.

In 1993 Ehrler investigated the concept of the C4 triturating proving

methodology through self-experimentation (Botha, 2010).

During Ehrler’s first homoeopathic trituration he experienced physical

and psychological symptoms and also obtained insight into the triturated

substance.

If a natural substance needs to be triturated as part of the

potentisation process, it is triturated to the 3CH level and then from then

onwards liquid potencies are generated.

Becker and Ehrler discovered that triturating a remedy to an additional

level, i.e. the C4 level, raised the healing potential of the remedy thus

revealing the essence of the remedy.

The methodology of this type of proving requires a group of provers to

participate in a process of trituration by hand and the proving substance

identity is unknown

(Hogeland and Schriebman, 2008). While the proving is being conducted

the prover will experience symptoms that are physical and psychological. The

provers will also

see images and ideas of the proving substance (Botha, 2010).

At the completion of each level of the trituration process the provers

had to record their feelings and impressions that were gathered during the

trituration. The trituration

to a C4 level of a substance occurs for a duration of 5-6 days. The

symptoms encountered by a prover on a single level will disappear when moving

on to the next level

of trituration (Brinton and Miller, 2004).

Becker presented Ehrler’s experiences during the 53rd

Congress of the Liga Medicorum Homoeopathica Internationalis in Amsterdam in

1998. Becker and Ehrler claimed that the C4 trituration level gave “a new,

spiritual dimension to the picture”, thus giving a deep knowledge and

understanding as to the homoeopathic potentisation (Becker and Ehrler, 1998).

This was received with mixed responses by the homoeopathic community.

According to Becker and Ehrler (1998) the mechanical friction with

lactose during the process of trituration is where the vital and valuable form

of the homoeopathic potentisation occurs.

The friction of the succussion with alcohol increases the rhythm of the

oscillation level (Becker & Ehrler, 1998).

Botha and Ross (2010) presented evidence of the physico-chemical

importance of trituration.

The efficacy and scientific footing of C4 trituration is disputable as

Becker cannot clarify as to where spiritual level images are derived from.

Timmerman was fascinated by Becker and Ehrler’s statements and she began to

investigate further in this avenue. Timmerman used the 4CH trituration level

and thereupon converted it into liquid potencies. Timmerman stated that she

gathered positive results in the treatment of chronicly ill patients. The 4CH

trituration provings are a debateable issue with homoeopaths who deem that

homoeopathic medicines should be processed as Hahnemann had advised. Dellmour

(1998) is of the opinion that symptoms collected from the C4 trituration

proving should not be entered into the materia medica. He believes that they

contradict the teachings of Hahnemann and outlines them as vague, illogical and

unhomoeopathic.

Botha and Somaru (2010) hypothesised that the remedies of the C4

trituration for each level of trituration revealed distinct effects.

2.4.1.1

C4 Proving At Durban University Of Technology

Ten provers form a stable proving group for a C4 trituration proving.

Botha (2010) conducted a C4 trituration proving of Protea cynaroides at

the Durban University of Technology. The trituration process produced viable

symptoms.

The group discovered that the intensity of the triturations they experienced

increased the more they worked together (Botha, 2010).

An other example of a profound C4 trituration proving conducted at the

Durban University of Technology was the proving of Vibhuti (Somaru, 2010).

Goote(2011) conducted a study to compare the symptoms derived from a C4

trituration proving with the symptoms displayed in a traditional proving of the

same substance found in the materia medica. The prover population consisted of

ten provers who were experienced in the trituration process but had no

knowledge regarding the substance being proved. Information was collected by

interviewing sessions and records kept by the triturators. The results of the

proving were that the comparison did not find a valid correlation between the

rubrics of the traditional provings of Borax 30CH and the C4 trituration

proving of Borax (Goote, 2011).

According to Goote (2011), although C4 provings were faster compared to

traditional proving methods and refined by Sherr it cannot be recommended as an

avenue of developing homoeopathic remedies to replace traditional proving

methods as the C4 proving will not produce a complete symptom picture.

2.4.2

Dream proving

A dream proving is similar to other provings in that it is a systematic

procedure requiring the development of uniformity with the influence of the

remedy on the vital force. The central focus is on dream symptomatology

although other levels of symptomatology are included (Kreisberg, 2000). The

concept that the dream state is altered by the proving reveals the mental and

emotional state of the prover. This provides a deeper connection to the remedy

picture.

Jurgen Becker began conducting dream provings at the Bad Boll seminars

25 years ago. This seminar took place twice a year for one-week at Bad Boll, in

Goppingen in Germany.

The seminar consisted of approximately 100 participants.

The proving was conducted by Jurgen Becker and Gerhardus Lang (Pillay,

2002). At these seminars homoeopaths presented their discovery of a

homoeopathic remedy that they felt strongly about and had proved the same

remedy thoroughly.

During the seminar a dream proving was conducted daily and the symptoms

were analysed on the last day (Pillay, 2002).

Many dream provings were conducted during Sankaran’s seminars at Mumbai

with his students (Dam, 1998). Sankaran states that in our dreams our actions

and emotions

are wholesome, pure and unblemished in comparison to our state of

consciousness where we are able to hide our true emotions. Therefore our

experiences in dreams reflect

our emotions towards certain incidents or events and experiences

(Sankaran, 1998).

The methodology of dream proving focuses on the extraction of mental,

physical and emotional symptoms by exposure of the prover to the remedy in one

of the following ways:

Consuming the remedy orally; Inhaling the remedy; Holding the remedy in

the hands for a certain amount of time; Sleeping on the remedy; By contact with

another prover who has taken the remedy; and present in the same room with

other provers (Dam, 1998)

A large part of the homoeopathic community believe that dream provings

are non-Hahnemannian provings (Dam, 1998). Dream provings are a debatable

aspect of homoeopathy. The interpretation of dreams can be deceitful because

dreams are one’s feelings and when a homoeopath prescribes a remedy the

practitioner needs to understand the individual as a whole and not only view

the mental aspect of the person (Brilliant, 1998).

According to Sherr (2003) dream provings are “partial provings” and beneficial

only to the extent that this is a short cut method to obtain the nucleus of a

remedy

(Sherr, 2003).

2.4.2.1

The advantages of a dream proving are as follows: It does not require

much commitment from the prover or supervision by the researcher so dream

provings are not intrusive (Fraser, 2010).

It has an easy and quick set up with an easy collection of data and

publication (Fraser, 2010).

Dream provings reveal dramatic useful imagery which allows for better

understanding of the remedy (Fraser, 2010).

2.4.2.2

The disadvantages of a dream proving are as follows:

The quality of the information obtained and reliability in this proving

is a disadvantage. Emotional symptoms are mainly produced whereas physical

symptoms are rare (Fraser, 2010).

There is difficulty in distinguishing between personality and the

proving for both the provers and the researcher as the proving of dreams is a

combination of the influence of the remedy and the provers own situation and

concerns (Fraser, 2010)

2.8

BLINDING

This was first adopted by the homeopaths to test substances. Kent

introduced the concept of blinding in homoeopathic drug provings. The writings

of Kent revealed that the concept of blinding was considered normal and routine

in homoeopathic provings by 1900 (Kaptchuk, 1997: 50).

The first double blind experiment was a proving of Belladonna.

Presently, most provings are blinded and the practice of the blinding technique

is widely recognised as a method to differentiate between the feedback of the

placebo from the reaction of the proving medicine (Ullman, 1991: 56).

Historically most homoeopathic proving substances were known to the

prover. The double blind methodology is standard in modern day provings where

the proving substance is known only by the researcher.

The provers are unaware of the proving substance. In a double blind

proving both the provers and researcher are unaware of who is taking the remedy

and who is on placebo (Sherr, 1994: 36).

Thus the possibility of bias is ruled out. Blinding can decrease the

different evaluation results but can also improve compliance of the provers.

At Durban University of Technology proving studies follow either a

double blind (Pather, 2008 and Somaru, 2008) or triple blind (Ross 2011) method

to ensure lack of bias. The process of randomisation is conducted

electronically by a homoeopathic clinician and lecturer in the Department of

Homoeopathy at Durban University of Technology as recommended by the Departmental

Research Committee.

2.9

RANDOMISATION

Randomised controlled trials are experimental studies to determine the

effect of an intervention by assessing the information gathered prior to and on

completion of the intervention. The objective of randomised controlled trials

is the comparison of intervention with a single or many other inventions or

without intervention.

These interventions are most likely clinical treatments but can also be

educational interventions (Levin, 2007).

The aim of randomisation in a double blinded proving explains that both

the provers and researcher are unaware of who belongs to the placebo or verum

groups.

Advantages of randomised controlled trials include:

Randomised controlled trials provide strong evidence of the efficacy of

a treatment (Levin, 2007).

The randomisation of the provers into the experimental and control

groups (Levin, 2007).

Allocation concealment ensures that allocation bias and confounding of

the unknown component are reduced (Levin, 2007).

Randomised controlled trials can be modified to answer a precise

question (Levin, 2007).

Disadvantages of randomised controlled trials include:

There is a high dropout when the provers experience undesirable side

effects of the intervention or when little incentive is provided to remain in

the control group (Levin, 2007).

Due to ethical considerations a research question may not be determined

using the randomised controlled trial design (Levin, 2007).

An observational design may be easier and cheaper to make use for a

descriptive overview (Levin, 2007).

Information is needed regarding the level of clinically significant

improvement and the conventional variation of development in the sample so that

the sample size can be calculated in the randomised controlled trials (Levin,

2007).

THE EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

The homoeopathic drug proving of Acacia xanthophloea 30CH was conducted

as a randomised double blinded placebo controlled research study. The sample

size of the study consisted of 30 provers who were selected after meeting the

inclusion criteria (Appendix E).

In the proving provers received the proving substance and the remaining

six provers received the placebo. The sample size adheres to the recommendation

made by standard international guidelines

as articulated in the “Homoeopathic Proving Guidelines” (Jansen and

Ross, 2014).

The powders were randomly allocated and both the verum and placebo

powders were identical in physical appearance and presentation. In a double

blind study both the researcher and provers are unaware as to whether they were

assigned the verum or the placebo powders. The randomisation method was

performed by Dr I Couchman an independent clinician and lecturer at the Durban

University of Technology in the Department of Homoeopathy, appointed by the

Departmental Research Committee.

The population of provers was made up of male and females in the age

range 18 - 59 years.

The study was conducted by two researchers A. Gobind and G. Zondi who

were responsible for 15 provers each. Within a group of 15 provers 12 provers

were allocated into the verum group and the remaining three provers were

allocated into the placebo group.

Each prover was allocated an individualised prover code, a journal and

pen prior to the commencement of the proving. During the duration of the

proving each prover was required to accurately record all signs and symptoms

that arose during the homoeopathic drug proving. As an „internal‟ control

all provers were instructed to record their „normal state‟ also known as

their baseline for one week prior to taking the verum/placebo powders

(Vithoulkas, 1986). Each prover received nine powders with instructions to take

one powder three times a day for three days. On completion of the proving

period the journals were collected. The symptoms experienced by the provers was

collected, collated and converted to materia medica and repertory format for

future use in clinical practice. A homoeopathic remedy image was formed with

distinct themes and characteristics which were subsequently compared to the way

in which Acacia xanthophloea is used in the African medicinal

tradition.

3.2

OUTLINE OF THE EXPERIMENTAL METHOD

1. The study was conducted by two M.Tech. Homoeopathy students under the

supervision of research supervisor Dr. M. Maharaj and co-supervisor Dr. C.

Hall.

2. The proving substance Acacia xanthophloea 30CH was prepared by the

researchers according to Method 6 (Triturations by hand) and modified Method 8a

(Liquid preparations made from triturations) as specified in the German

Homoeopathic Pharmacopoeia (GHP) (Appendix G).

3. Provers were recruited by advertisements placed on notice boards at

various sites at the Durban University of Technology and by personally inviting

potential provers (Appendix H).

4. The researcher conducted interviews with prospective provers who were

screened for suitability and the researcher questioned the provers about their

medical history and lifestyle to determine if the provers met the inclusion

criteria (Appendix E).Those provers who met the inclusion criteria continued to

the next procedure in the proving.

5. After the selection process all provers attended a pre-proving

seminar which was conducted by the researchers. During the seminar the

procedure of the homoeopathic proving was explained to inform provers of what

was expected of them during the proving (Sherr, 2003). All aspects of the

research study were explained to all the provers. The seminar provided all

provers the opportunity to clear up any queries they had regarding the research

proving study.

6. Provers were randomly assigned by an independent clinician into the

verum or placebogroups.

7. The researcher and each prover agreed to meet on an allocated date

and time.

8. At the consultation each prover received a preliminary letter of

information outlining the procedure of the proving. The prover was required to

sign the preliminary consent form. Provers between the ages of 18-21 needed

consent from their parents or guardians prior to participating in the study

(Appendix A).

9. The provers were guided through the letter of information (Appendix

D) and signed the informed consent form.

10. A detailed case history of each prover was taken. Thereafter a

physical examination was conducted (Appendix C).This served as an additional

screening procedure.

11. After the physical examination a pregnancy test (urine test) was

conducted on all female provers. Those provers with a negative result was

accepted into the proving.

A positive result of the prover was deemed to be an exclusion criteria

(Appendix E).

12. Each prover was allocated with a personalised prover code, pens, and

a journal with a prover code corresponding to the prover number in which to

record their experiences during the proving.

All provers also received a personal copy of the preliminary letter of

information and letter of information containing instructions to be adhered to

during the proving as well as proving information about the homoeopathic drug

proving.

In addition, each prover received a list of contact numbers of the

research investigator and supervisors.

13. All provers were informed of the date of commencement of the proving

after the case history and physical examination was completed.

14. Each prover received an envelope labelled with their corresponding

prover code containing 9 powders (verum or placebo) with instructions to take

one powder 3x daily.

15. The provers began capturing their daily symptoms on the date

assigned in their journals with a minimum of three entries daily for one week

prior to consuming the proving substance. The “normal state” of a prover (baseline)

is important as it shows the standard state of health of an individual prover.

This constituted the control for the comparison of the symptomatology for the

pre-proving and post-proving periods.

16. Upon the completion of the pre-proving week each prover commenced

taking their powders with a maximum of 3x daily for three days or until

symptoms appeared.

No further doses of the proving substance would be taken if symptoms

arose although the prover continued to record their symptoms throughout the

proving. A minimum of three recordings a day was required for six weeks. The

provers were required to accurately and diligently record their symptoms

experienced daily.

17. In the first week of the proving the researcher communicated daily

with each prover telephonically to discuss their symptoms. This ensured

compliance and accuracy in symptom recording.

18. The prover would not take any further doses of the proving remedy if

symptoms were experienced. The prover discussed the symptomatology experienced

with the researcher to determine if the symptoms were as a result of the

proving remedy. The powders were immediately discontinued if the symptoms were

as a result of the proving remedy.

19. During 3 days if all 9 powders were taken and no symptomatology

occurred the prover was required to continue making journal entries until

proving symptoms began or

till the end of the proving period.

20. Each prover was required to record in the journals until all their

proving symptoms had subsided.

21. In the second week, telephonic contact with the provers by the

researcher occurred every second day and in the third week contact was

maintained every third day.

The researcher contacted each prover once only in the fourth week. The

prover would continue to record all their symptoms until the complete duration

of all proving symptomatology.

22. Provers continued journaling for a post-proving observation period

of one week. This was to ensure no recurrence of proving symptoms.

23. If a prover had an adverse event then they would have been antidoted

but remained a part of the study by continuing to record symptoms.

24. The study lasted six weeks which included one week pre-proving

period and one week post-proving observation phase.

25. After six weeks the journals from each prover was collected.

26. A follow-up case history was taken and physical examination was

conducted on each prover.

27. The data collected during the research was carefully studied and the

process of symptom extraction initiated.

The symptoms that arose in the study was screened in accordance with the

symptom inclusion and exclusion criteria.

28. The symptoms experienced by the provers was collected and collated

then converted to materia medica and repertory format with subsequent comparison

to the African medicinal tradition.

29. The researchers were unblinded to the verum / placebo assignment to

facilitate distinction between the verum and placebo groups.

3.3

THE PROVING SUBSTANCE

3.3.1

According to Hahnemann the 30CH potency was most valuable for the use of

determining the dynamism of medicinal substances in provings. Hahnemann defined

this proposal in Aphorism 128 of The Organon of the

Medical Art (O’Reilly, 1996). Initially Kent questioned this proclamation but

later supported the use of the 30CH potency.

Stomach: Thirst for large quantities

(often/unquenchable/before vomiting)

Vomiting - < after breakfast/> drinking/sudden/after eating

(eggs)/inclination to vomit

Abdomen: Heaviness

Distension

Rectum: Abscess

Constipation (+ flatulence/+ stomach complaints/difficult stool/in

women)

Constriction – night/painful/during urging to stool

Rectum: Diarrhea (+ weakness/< after eating)

“As if empty”

Flatus

Pain after/during hard stool

Stool: Black/copious/dark/frequent (at night)/hard/offensive/watery

(at night)

Bladder: Inflammation + burning urine

Pain – burning (evening)/(<) during urination/< beginning +/ o.

end of urination

Retention of urine

Urination frequent

Female genitalia / sex:

Bleeding after coition

Sexual Desire diminished

Eruption – itching/nodosities/painful pimple/pustules before menses

Heaviness during menses

Itching in vagina

Sexual Desire increased

Leukorrhea cream like

Menses - bright red (clotted)/partly clotted

Menses – brown/changeable in appearance/copious (daytime)/dark with

clots/too early/scanty too late/membranous/during menopause/offensive/painful

(+ complaints

of ovaries)/pale/protracted/scanty/”As if copious”/too short/thick/thin

(with clots)/watery

Pain – during menses

Chest: Anxiety heart

Itching of nipples

Oppression anxious

Pain (r./constriction/cramping cutting/< exertion/< motion/cutting

pain [middle of chest – morning/afternoon/evening (ext r. side)/<: motion/expiration/inspiration;]/>

rest/

Palpitation - with anxiety

Back: l. /r.

Pain [morning/afternoon/lumbar region/aching/< bending/<

cold/after taking a cold/drawing/l. stitching pain/lumbar region (/in afternoon

“As if sprained”/sore/”As if broken”/> rubbing)/< motion – drawing pain

Pain – r. (stitching)/< motion of shoulders/”As if someone is

poking”/> rubbing/scapular sore/< sitting down/spine (aching/sore)/<

turning (drawing/head)/unbearable/< standing (lumbar region)

Tight feeling

Extremities: Feet icy cold

Cramps in feet

l. foot < walking/l. foot feels hot uncovering

Heat in upper arms

Numb legs morning (r./< motion/< rising/< standing)

Pain in feet - ankles [(l./after walking)/elbows (l./drawing/<

motion/ext. head/feet (morning/l. heel/pulsating/< after walking/sore (at

night)/< standing/< stepping

Pain in - forearms (morning/daytime/aching/drawing downward/near

elbow/< after exertion/ext. elbow/ext. hand/< lying)

[Ruth Heather Hull]

A proving is a controlled, reproducible and hence reliable method used

to determine what a particular substance does to a healthy person. A potentized

remedy made from

a substance is given to a group of healthy people and all their

symptoms, physical, mental and emotional, are recorded and from these symptoms

a remedy picture can be developed. This remedy picture is then recorded in the

materia medica

[Jan Scholten]

What are provings?

The word proving has several aspects. One is to prove, to establish as a

fact, to make it certain. Another is to experiment or to test. This aspect is

marked in the Dutch word "proeven", which means to taste. Taste and

test come from the same origin.

Provings are procedures where provers are exposed to a substance or

influence and invited to express the impressions of that exposure. The

procedure can be compared with radio or television broadcasting with a

transmitter and receiver. The remedy can be compared with the transmitter, the

prover with the receiver. The procedure has several aspects: the remedy, the

prover sensitivity and the prover attention.

1. Remedy

The remedy, or any other influence, is the signal. The signal has to be

strong enough to be received. In provings the signal can be made stronger in

several ways.

One obvious way is to give the remedy in a crude form, as is done in

intoxications. This has the danger of overloading and ruining some parts of the

receiver, it makes the prover ill.

Another way to strengthen the signal is to give repeated doses. People

have also tried to strengthen the signal by using higher or lower potencies.

The experience of Sherr and myself is that it’s hard to discern in provings

which potencies are stronger than others.

2. Prover sensitivity

The sensitivity of the provers is crucial for the proving. Some provers

hardly get any symptoms or they hardly dare to trust their impressions, in

which case a good supervisor can be of help to strengthen their trust.

Sherr stresses the importance of sensitive provers in the proving: “One

sensitive prover can make a whole proving, bringing to light the most profound

aspects of the remedy

in a most beautiful way” and “Often the most important proving symptoms

are brought mainly by one or two sensitive provers, the others serving to fill

out the bulk of common symptoms.” One 'master prover' in his provings has been

crucial; some provings only made sense after she joined in again.

Another way to amplify the result of the proving is to involve many

provers. Many provers can receive more information than one and different

aspects of the remedy.

Another way is to repeat the provings, in different times and

circumstances, with different provers and in different cultures. This aspect

will also be discussed below in

the 'Prover attention'.

3. Prover attention

The attention of the prover is crucial. The attention of the prover can

be compared with the tuning of the receiver. A radio receiver will only amplify

what it’s attuned to;

other senders will not be amplified and heard. When the attention of the

prover is not focused on the remedy, all kinds of other influences can present

during the proving.

It’s like a receiver that has to be tuned to the right signal. Hahnemann

was already very much aware of this fact, as he shows in Aphorism § 126 of the

Organon:

“During the whole time of the experiment he (the prover) must avoid all

overexertion of mind and body, all sorts of dissipation and disturbing

passions. He should have

no urgent business to distract his attention. He must devote himself to

careful self-observation and not be disturbed while so engaged.”.

There are several techniques to enhance the attention of the prover.

Frequent talks with a supervisor are a good help and according to Sherr

indispensable.

Another technique is meditation. Then, almost all the attention is

directed to the remedy, although it’s by no means a guarantee that other

influences will not come in.

This aspect of attention is crucial. The opposite of good attention is

disturbance or noise. The incorrectly attuned receiver will show another sender

or just noise and rumble. Attuning a prover is not as easy as attuning a radio

receiver. Other influences cannot be excluded so they have to be taken into

account. In every proving there will (probably) be incorrect information and

disturbances. The topic of incorrect proving information has been for the most

part neglected in homeopathy. Hahnemann excluded the possibility in paragraph

138 of the Organon. There are no procedures for removing incorrect information

out of our repertories and Materia Medica (except obvious mistakes like

confusion of "con" and "com"). The homeopathic community

behaves as if mistakes don’t exist. In my experience there are many errors. The

problem is how to sift them out.

Using more provers in one proving or repeating provings in different

circumstances and cultures is a means to single out disturbances. A symptom that

is produced by only one prover has a higher likelihood of being just a symptom

of the prover. The fact that only one prover has a particular symptom is no

guarantee that the symptom comes from a personal disturbance. Sherr has pointed

this out clearly and it’s also my experience. One prover can perceive the

essence of the remedy and even know that it is the essence. Using groups is

also no guarantee against group disturbances.

A frequently encountered disturbance is “homeopathic thinking” as most

provers are homeopaths. This is a form of the more general cultural

disturbances. A nice example is a proving by Sankaran of Ferr-met. Many provers were

dreaming about marriage, but it was not because Ferrum as such has anything to

do with marriage, but that the symptom “being forced to” of Ferrum is connected

to marriage in the Indian culture.

Disturbances can be seen as the consequence of being out of tune, or

being attuned to something else, other than the remedy we want to “measure”.

Several kinds of disturbance can be recognized:

1. Event disturbances

All kinds of events happen at the same time as the proving. It’s almost

impossible and never done to isolate the provers from all impressions other

than the proving substance. Eating is an immediate influence just as not eating

is.

A nice example of an event disturbance is described by Shore in the

proving of Pelecanus occidentalis: “Everyone is aware of the terrorist attacks on New York and

Washington DC on September 11, 2001. These tragedies happened one week after we

started the proving. This event had an impact on all of us and colored the

proving in ways we cannot predict or separate out”. This event is obvious for

the impact it can and will have. But minor events too can influence the

proving, like a dinner with friends, the kind of food eaten, a television

program or a story in a journal or a quarrel with a family member.

Events can also be subtler. In meditation provings one clear event is

the meditation. This produces meditation symptoms like light feeling, floating

sensation, tingling, hyperventilation, awareness of heartbeat, respiration and

of the body. One can find symptoms like these in all meditation provings and

most of the time they say nothing about the remedy.

One of the problems is to discern if the event belongs to the remedy or

not, if it’s accidental or synchronicity. There’s no way beforehand to know for

sure which of the two is the case.

2. Personal disturbance

Every prover brings with him his personal make-up, ideas, character and

state. One could call them stored events, as they are the consequence of events

in the past and adaptations to those events. They are fixed, conserved and can

be triggered by new events or come up by themselves. Events like provings can

trigger them just as much.

A nice example has been published by Vermeulen in Dynamis. He compared

the provings of six remedies and found out that they all had the symptom of

misanthropy, aversion to people. It turned out that that symptom was every time

coming from the same prover. That prover's character had plenty of timidity and

misanthropy.

Group states can also be of influence. An example is the proving by

Jürgen Becker of Ferr-p., which produced the symptoms of transvestism. In my

experience that symptom doesn't belong to

that remedy. I haven’t seen it in my own and other homeopaths' cases and

it doesn't fit in with the Element theory.

Every prover brings with him a lot of themes. They can arise from

himself, but can also arise in these cases from his family, the group that he

works in, his culture or the history of the world.

It’s hardly possible to discern during the proving whether symptoms

belong to the remedy or not. Even when a symptom is typical of the prover it

might be that the remedy has that symptom too

and that might be the reason it could be triggered so easily.

Conclusion

Provings have only a few principles: remedy, prover sensitivity and

prover attention. This leads to many techniques such as intoxications, full

provings, dream provings and meditation provings.

In each of these, many variations or completely new forms can be

designed. Examples are bath provings (dissolving an essential oil of a plant in

a bath and sit in it), image provings (looking at a plant or an image of it and

meditating on it), thought provings.

None of them can guarantee complete and accurate results. Some

homeopaths have the idea that dream or meditation provings cannot give correct

results. This can be refuted with an example.

In both Cerium provings at the end of "Secret Lanthanides",

the symptom of being in a bell-glass was experienced. This symptom has been

verified in many Cerium cases.

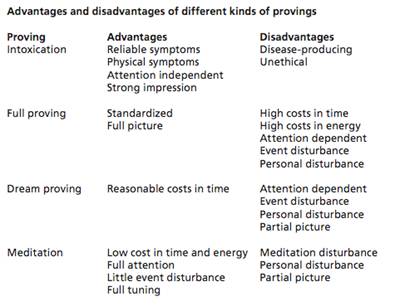

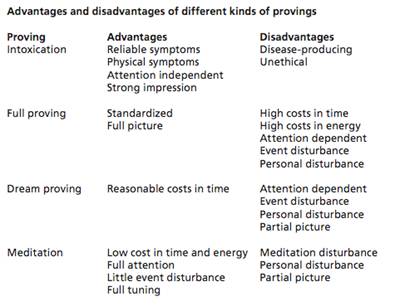

All provings have advantages and disadvantages and I’ve placed some of

them in the table below.

For me the meditation proving is often the most convenient and helpful.

It gives results fast and with little effort. The disadvantages are that the

picture will not be complete and can be incorrect in parts. But that can also

be the case with other provings. In my experience, meditation provings often

are quite reliable and give the essence of the remedy, more so than dream

provings. For others the opposite can be true.

When used with care, the information in the meditation provings in

"Secret Lanthanides" can be and has been very helpful in the

development of the remedy pictures. I publish them so that the reader can have

a fuller picture of that development.

|

Provings |

|

|

|

Intoxication |

Reliable symptoms |

Disease producing |

|

|

Physical symptoms |

Unethical |

|

|

Attention independent |

|

|

|

Strong impression |

|

|

Full proving |

Standardized |

High cost in time and energy |

|

|

Full picture (?) |

Attention dependent Event disturbance Personal disturbance |

|

Dream proving |

Reasonable cost in time |

Attention dependent Event disturbance Personal disturbance Partial picture |

|

Meditation |

Low cost in time and energy Full attention Little event disturbance Full tuning |

Meditation disturbance Personal disturbance Partial picture |

[Victoria-Leigh Schönfeld]

Historical Perspectives of Provings

Samuel Hahnemann, the founder of homeopathy, was the first to experiment

with provings.

In the year 1790, Hahnemann was contracted by a physician of the time,

named Cullen, to translate “A Treatise Of Materia Medica” written by Cullen

into the German language. As he was reading through the material, he disagreed

with Cullen’s explanation regarding the mechanism of action for the treatment

of malaria using the bark of the Cinchona tree. Cullen had claimed that the

curative

action of Cinchona officinalis (an existing treatment for malaria) was

due to its bitter taste. Hahnemann, disagreeing decided to experiment with the

substance by ingesting the bark himself.

After taking it for several days; Hahnemann began to experience symptoms

similar to that of a malarialinfection.

Once he stopped taking the Cinchona bark, his symptoms ceased and his

health returned to what it was prior to its ingestion. Soon afterwards, Hahnemann

experimented with other substances in a

Similar manner and came to the conclusion that a substance can cure the

symptoms it induces, or “like cures like” (De Shepper, 6 2005:27) therefore

discovering The Law of Similars.

H. continued experimenting with many other drugs on both himself and 64

other volunteers, determining the therapeutic potential of 101 remedies (Louw,

2002:23). Modern provings are still conducted largely according to the basic

methods of Hahnemann. Sherr, a contemporary international authority on

homoeopathic proving currently bases his methodologies largely on the

principles of H., but has modified them to relate to modern science (Sherr,

1994).

Even though the “Law of Similars” was said to be discovered by H.,

treatment by ‘similars’ was hypothesised significantly before Hahnemann’s time.

Hippocrates was involved with a similar theory in ancient times (Walach,

1994:129), as well as Galen in the 2nd Century A.D. who tested his

medicines on the sick and on the healthy. Paracelsus too, in the 16th

Century observed the effect of substances on healthy people to determine their

therapeutic properties however neither Paracelsus nor Galen undertook these

activities systematically as did H. (Coulter, 1975:442). Vithoulkas (1980:97)

states that provings are the introduction of a substance into the (human)

organism which is very high in dilution, in order to disturb and mobilize the

defense mechanism. According to Taylor (2004:5), in response to the proving

drug “the defense mechanism of the individual produces a variety of symptoms on

the mental, emotional and physical levels. ” This variety of symptoms is then

characteristic of the peculiar and unique nature of the substance.”

The curative response occurs when

the corresponding substance is given in a highly diluted format, which causes

the individuals immune system to remove the morbific picture of symptoms (i.e.

the symptoms of the disease), and in doing so the induced process does not harm

or compromise the patient’s immune system any further. Vithoulkas (1986:97)

suggests that in order for symptoms to be produced, the exciting cause should

be strong enough to mobilise the defense mechanism and the person should be

sufficiently sensitive to the unique vibratory frequency of the substance.

The medicine is given in subtle doses where the morbific symptom picture

is lifted without harming or weakening the patient further.

Proving methodology

Although H. was the first to formally conduct homoeopathic drug provings

establishing the foundation on which contemporary provings are based, he did

not incorporate any form of control or blinding into these experiments.

Although H.’s experiments yielded reliable results, his proving

methodology would not be considered to be reliable by modern standards for

clinical trials, in addition the expectations of provers following the H.n

proving methodology would be considered unrealistic in modern times, as he

insisted that his provers follow a strict diet and lifestyle, so as not to

taint the action of the remedy (Wieland, 1997:229).

Even though H.’s basic methodologies are still valid, modifications have

been made to the original methodology in keeping with the requirements of

modern scientific standards of experimentation.

Riley (1997) states that the value and quality of homoeopathic drug

provings will be improved if a consistent, systematic and scientific

methodology is utilized when conducting provings. Contemporary provings now

take the form of placebo controlled trials and incorporate double or even

treble blinding in order to control variables (Sherr, 1994). The concept and

principles of blinding

was introduced first by Gerstel in 1843 whilst proving Aconitum napellus

and double-blinding was introduced in 1906 by Bellows whilst he was reproving

the remedy Atropa belladonna

(Demarque, 1987). The concept of

double-blinding in a homeopathic proving implies that the researcher and

provers are unaware of the proving substance and is a means of protecting

against any bias from both parties (Sherr, 1994:36). Riley (1996) also states

that the use of placebo control and double-blinding promotes a self-critical

attitude in both the provers and the investigator.

Vithoulkas (1980) describes an extensive and rigorous regime for the

process of a proving. He prescribes a method that includes the provers

relocating to a more natural environment to optimise their health; in addition

he requires the provings to involve a large number of provers (50-100), of

which 25% are to form a placebo group. Vithoulkas’ prescribed time frame is

extensive, and the potency

applied is that of many ascending potencies over a protracted period of

time.

Vithoulkas’ method requires the experiment to take place involving three

different nationalities of provers comprising three different groups, in three

different geographical locations (Vithoulkas 1980:149-152). To follow this

methodology would prove to be unrealistic and prover compliance in modern times

would be very poor, in addition such a proving would prove very costly and time

consuming.

More contemporary proving methods known as ‘dream provings’ have become

popular in the last 30 years, and were first conducted by Becker (Dam, 1998).

There are no strict standardisations for dream provings, and they are

usually single blinded studies that focus mainly on dreams the provers

experience in response to the proving substance, although physical symptoms

during these provings do occur (Botha, 2011:16). Pillay (2002) conducted a

comparative study of two proving methodologies of the same proving substance

Bitis arietans arietans;

the research showed a result of 93% correlation to the symptoms that

were produced in the H. proving of the same substance, Bitis arietans arietans

conducted by Wright (1999). Pillay (2002) standardised the proving by

administering one single dose of the remedy taken sublingually at bed time

(Botha, 2011:16). The provers were to then record any dreams or other symptoms

that occurred thereafter. Even though a number of dream provings have taken

place recently, Sherr (1994) refers to the dream proving as only a “partial

proving” as he believes that it is a short cut into the inner essence of a

remedy, and that the totality of symptoms as well as long term symptoms are

missed by using these types of methods (Sherr, 1994:16).

Sanakran follows a protocol that is said to be seated between the

methodology of dream provings, and classical Hahnemannian provings (Botha,

2011:21). These provings are single blinded provings, the symptoms that he

concentrates on are the physical and emotional symptoms, as well as dreams.

According to Botha (2011), these provings are viewed to be similar to Sherr’s

methods, and are

considered to be a “halfway method” that lies between the Sherr and

dream proving methodologies.

Subsequently Sherr, (1994) published guidelines for provings, these

methodologies are an add on to the classical Hahnemanian method. Sherr (1994)

believed that it was important to maintain the modern lifestyle, as they are

only obstacles for cure, in contrast to Hahnemans strict conditions regarding

diet and lifestyle throughout the period of a proving. Sherr’s methodology

includes a

double blind, non prejudiced trial (Sherr, 1994:6), and is amongst the

most popular methodology applied at the Durban University of Technology (Botha,

2011:20).

The International Council for Classical Homoeopathy (ICCH, 1999)

attempted to standardise the conducting of homoeopathic drug provings. Their